There is a reality that communication professionals seem to forget, or many didn’t even know to begin with: the whole foundation of communication (PR, advertising, others) depends on human behaviour.

It depends on how human beings think; how they speak; how they act; how they react; and, as social media has made abundantly crucial these days, how they share. And human behaviour is, after all is said and done, a science.

There is a reason people interact differently with a retweet than with an original tweet. There is a reason Instagram posts get more engagement at a particular time of day and why readers respond to particular headlines when they see them. There is a reason people share some things in a frenzy, and ignore others.

There are patterns, there are correlations and similarities, there are root causes and alignments.

There is a reason geography is destiny, and demography is destiny. There is a reason people react the same way if they belong to a particular part of the country, and a particular age group. It’s either about this demography or that geography. There is a reason polling, targeting, and psychographic analysis leads to actual results. There are trend lines and micro trends.

It’s the entire science of human behaviour. And the truth that psychologists and neurologists and sociologists studying everything from food to running large organisations will tell you is this: the phone lines might connect faster, Internet move at speed of light, and cars gotten bigger, but human beings still behave in essentially the same ways.

They share gossip which they find interesting; men respond with erections to alluring nudity; people form cliques for validation; people act in ways that emphasise how they want the world to see them.

The entire architecture of communication depends on one immutable reality of human behaviour: word of mouth.

When all is said and done, human beings talk to themselves one on one – at the mall, at the dinner table in church, at the club, around the office water cooler.

This means we are still receiving and disseminating and acting on information essentially the way we were many decades ago – when the primary means of mass communication for many Nigerian communities was the village square.

People came in to the village square when they had to: by the king’s orders (captive audience). Other times people came in when they were attracted to what was happening (raving fans). They reacted, and lived their lives, based on what they heard and ultimately based on what they feel about what they heard.

Let’s have an example:

What if the town crier went around the village announcing that an important masquerade would be performing at the square every night?

People go there on Day 1, and the masquerade is there on time, on point and they have an incredible time.

The next day they come but he only performs for 10 minutes, unlike the two hours of the day before. And he treats the audience with disrespect.

The next, day he doesn’t show up.

The next day he doesn’t show up.

And then on and on and on for 15 days he doesn’t show up.

Of course, by the third day, the vast majority of those people would have left. They won’t keep coming back. Even if the king insists, they would yet be some holdouts still offended by the cavalier treatment.

If for any reason the town crier comes announcing on day 15 that the masquerade will be back on day 16, people are very unlikely to go through the trouble because they have been disappointed previously.

The advertised product didn’t behave in predictable, consistent, trustworthy ways.

All of what we described above is the field of consumer behaviour.

Humans beings, primal as ever, react in the same way as they always have to basic stimuli – excitement, disappointment, love, fear, hope, strength, satisfaction, joy, expectation.

Unfortunately, communication professionals seem to forget this when they write press releases, or build adverts, or design events. They seem to assume human beings will behave in unnatural ways.

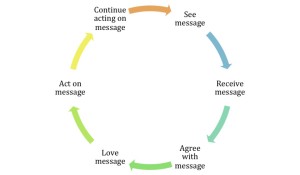

Whatever makes them forget is the reason they also forget that at the base of messaging is the simple core: all communication leads directly to word of mouth.

When AY advertises Maltina sponsorship of his show on a billboard, you note it down, and (if you live amongst human beings like the rest of us) you generally ask a friend physically or on social media: How was the show last year? Or you say to someone beside you: ‘Ol’boy we suppose show for Eko Hotel o’ Or something.

That process of word of mouth communication is what eventually leads to a buying decision.

The entire architecture of the AIDA Attention-Interest-Desire-Action loop – between Desire and Action – usually turns on that curve of word of mouth.